Jim Tressel

Big-10 Head Football Coach, University President, Hall of Fame Recipient, Avid Reader and Youth Mentor

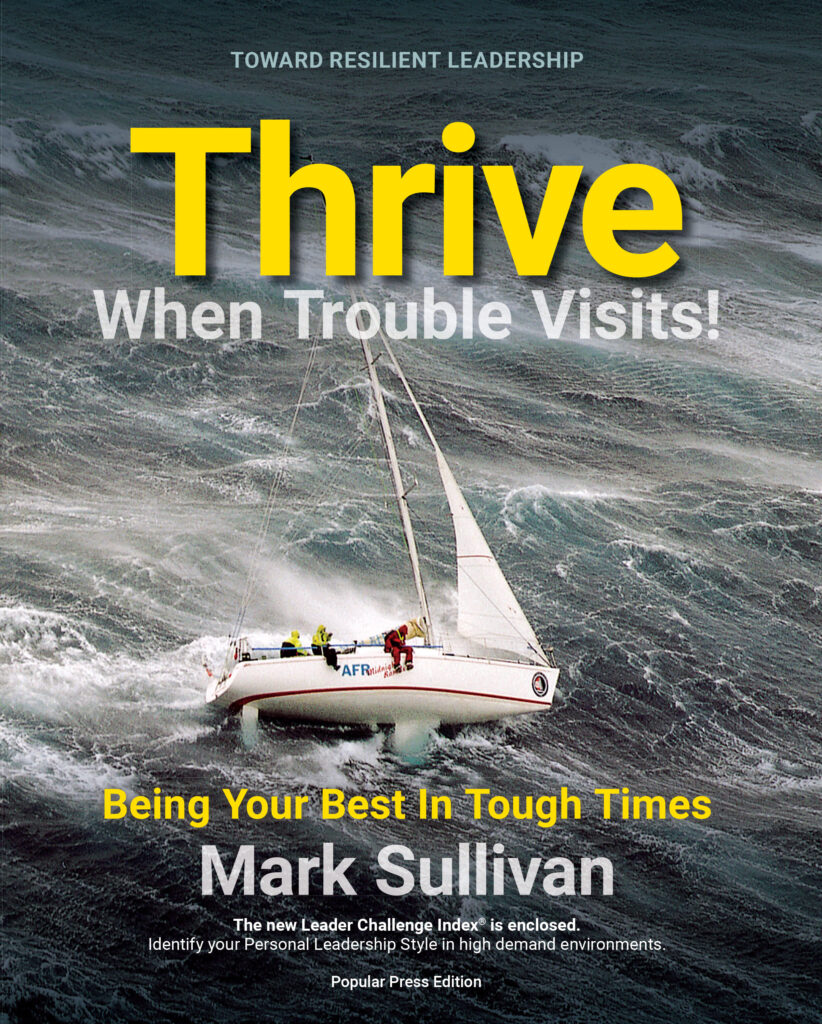

If you enjoyed this story, consider ordering Mark’s new book.

Permission Granted to Distribute by Signature Contributor

Sports, Media, and Entertainment Services

Frank Abagnale

Master Storyteller, Motivational Speaker, Moralist, Mentor, Reformed Con Artist (Featured in Hollywood’s Film, “Catch Me If You Can Played By Leonardo DiCaprio)

The cashier had given him too much change. Frank Abagnale sat in the Wendy’s drive-thru, his three sons in the car, and counted what was in his hand.

Change for a $20 bill, not a $10.

“I’m sorry,” he told the girl in the window, handing back the cash. “You made a mistake.”

His boys, the oldest just 12 at the time, couldn’t believe it. As they pulled away, one of them muttered what they all were thinking.

“Dad, you could have kept that change.”

Abagnale pulled the car over.

What he said next would have stunned anyone who thought they knew legendary con man Frank Abagnale.

Decades earlier, Abagnale was a young man—a kid, really—in a rush to prove something. His impatience led him high above the clouds.

“Ladies and gentlemen, this is your captain speaking. The forecast today to beautiful Los Angeles is sunny with a high of 85 and scattered clouds. We’re looking forward to a smooth journey with our fellow passengers, and we thank you for flying with us. Now sit back and enjoy the ride.”

As the aircraft lifted into the luminous sky, a wave of adrenaline awakened every nerve in Abagnale’s body. Decked out in a formal black fitted blazer and trousers, paired with the classic gold wing pin and embellished cap, he assumed a seat in the cockpit, hitching a ride with the pilots steering the aircraft. Although internally rattled, he couldn’t show it. He had to preserve his complicated ruse.

The 16-year-old secured a front-row seat to the most extensive landscapes and oceans the world has to offer.

When the wheels finally hit the runway, phase two of Abagnale’s deception was in full effect. The impeccable uniform and forged pilot certification provided limitless entry into the vaults of oblivious bank agencies. His cunning smile and prematurely graying hair sealed the deal. Using a stack of forged checks and his temporary addresses of lavish hotels, he could seamlessly accumulate wealth at a staggering pace.

Abagnale was living out a picturesque fantasy as a teenager. The movie Catch Me If You Can, where he was played by a dashing Leonardo DiCaprio, chronicled his glamorous, felonious exploits. The world was his oyster, and he gobbled it up. He guzzled century-old red wine and snacked on the finest caviar at soirees around the globe. Beautiful women would flock to his side, hoping to accompany him on his next grand adventure.

The risks were great, but the highs were greater. Over the next few years, Abagnale became a master of disguise. He nimbly juggled his aliases, transforming from a pilot to a doctor to a lawyer—whatever persona suited his needs. Each move left his heart pounding.

What trace was he leaving behind? Which trip would be his last?

If you saw the movie, you know that answer came soon enough. The FBI did, eventually, catch up with Frank Abagnale.

He was swept off to prison, and society thought that would be the last they’d ever hear of him. But the very talent that landed him behind bars also opened a one-of-a-kind opportunity. The Federal Bureau of Investigation knew they had met their match. Instead of throwing away the key, they decided to employ his expertise for the greater good. That is, to teach agents to think like a criminal in investigating the seedy, dark underworld of schemes and scammers.

At least, that’s how the FBI saw it. Abagnale had other motives. He saw an easy way out—a shot at freedom, if he was willing to play the FBI’s game.

“I try to be very, very honest about this,” he said. “After two years, I didn’t come out of prison as a reformed person. I didn’t come out of prison saying I saw the light and prison changed me and from now on, I’m going to be a good guy and I’m never going to break the law again. When the government offered to take me out of prison at 18, I saw that only as an opportunity. I had an opportunity to get out of jail, so of course I was going to say yes.”

He was still thinking like the kid who’d pulled off an extraordinary con, fleecing banks and cashing huge checks against multibillion-dollar corporations. But working every day with high-profile FBI agents began to alter the way Abagnale saw the world. The good guys wore off on him. He stopped thinking about what he could gain by swindling industries and started worrying about who he might be hurting in the process.

And then there was the woman.

Her silky brown hair and tender heart drew him in like a magnet. She was one of the first people who saw him for who he truly was—and so he told her who he truly was. He broke FBI protocol and revealed his true identity after a six-month undercover assignment.

“She accepted me for who I was,” he said. “We went on to get married against the wishes of her parents. The truth is, she changed my life. She turned my life around. She had faith in me, she trusted in me, she believed in me. I didn’t have a dime to my name.”

For the first time in his life, Abagnale began to believe that being who you are—your genuine self—could attract the right opportunities and bring the right people into your life. As the self-confidence poured back into his soul, protecting others became his new high. He boldly walked into a bank and requested that leaders listen to a presentation he had prepared—free of charge, unless the information provided to them was useful.

After that day, his name spread like wildfire throughout corporate America—this time, in a positive way. Companies were reaching out left and right to get a piece of Abagnale’s wisdom. Providing simple solutions to serious issues, Abagnale touted education as the best tool for fighting crime. He taught to ways prevent crimes in the first place to avoid desperately trying to pick up the pieces when the scam fell apart.

Of course, he hasn’t been able to completely rehabilitate his image. Many only know him from the Catch Me If You Can antics of his late teen years. Even with a half-century of distance between him and his misdeeds, he finds that white-collar crimes and major fraud still evoke the name Frank Abagnale.

He’s OK with this. He has something greater than his reputation to worry about.

“What is most amazing to me—well, I say to myself, ‘I am a former criminal,’ but I did these things when I was 16 years old,” he said. “Now I’ve spent an entire career working with my government. I have worked with the biggest companies in the world. I brought three great sons in the world and have been married to my one and only wife for over 40 years.”

What will determine his legacy, he said, is how his wife, children and grandchildren see him—and the way they navigate their own worlds with integrity.

Which is why, on that day so many years ago, as he drove off from the Wendy’s drive-thru, he seized the opportunity to teach his children a lesson it had taken him a long time to learn.

He told his sons exactly why he didn’t keep money that didn’t belong to him.

“I pulled the car over and explained to them that, one, that would be wrong. And two, that young girl, who is probably in high school, would have probably lost her job when the register didn’t check up at the end of the day—and was it worth the 10 bucks I might have made at the end of the day?”

We’re told life is short, Abagnale said, but it can be remarkably long. Bad decisions early can leave a lifetime of regret. He counsels young people to make sound decisions early in life—to put yourself in the best position to be your most authentic, honest self.

Frank Abagnale found the strength to shed his disguises—will you?

If you enjoyed this story, consider

nec gravida tempor dolor convallis. facilisis in nec gravida tempor dolor convallis.

facilisis in facilisis tempor libero, orci cursus nec orcial nec gravida tempor dolor convallis

2-way access:

- To purchase the THRIVE book separately, click “Buy Now”

- Want to purchase only the Toolkit? Click on the ‘Get Toolkit’ button to access it instantly