James C. Lawler, JD

Four Star General Shuttling Between Mindsets in A Combat Theatre

General Stanley McChrystal comes from a tradition of commitment; both his father and grandfather served in the U.S. military. Like his father before him, McChrystal graduated with a B.S. from West Point Academy in 1976, and in his long career of military service, became the general in command of the American and international forces in Afghanistan.

Rising through the ranks, McChrystal lived with military discipline and gained insight while serving around the world in high-stakes assignments. Like all successful military leaders, he learned to think systemically. However, he is also known for advancing more creative approaches to new forms of warfare in the later years of his career, especially as he gained experience and responsibility.

McChrystal was appointed to serve as Commanding General to the Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC), the military’s premier counterterrorism force, in September of 2003. When he took that job, the group was operating under traditional systems that were effective in quickly destroying hierarchical terrorist networks. But it was not as adaptable as the new insurgencies emerging in more local, loosely configured adhoc terror groups in the Middle East.

McChrystal could see that JSOC needed to change; instead of asking his soldiers to operate in carefully delineated silos, he began to integrate intelligence, combat, and strategy communications within the JSOC community. The new structure made his troops more agile and effective resulting in the high-profile capture of Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein and killing of Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, the terrorist leader of Al-Qaeda in Iraq.

In June of 2009, McChrystal was appointed to lead American troops in Afghanistan, and shortly thereafter assumed command of NATO operations. Again, he thought about the war in a new way. He was a leading proponent of the “surge” strategy in Iraq which would require additional troops be sent in to wipe out enemy combatants. More simply, the strategy was to add more troops with the goal of ending the conflict faster.

In 2010 though, after an off-the-record quote appeared in Rolling Stone Magazine which was critical of the administration, McChrystal began to think systemically again. The story appeared online at about 2 a.m. in Afghanistan. He remembers, “my military assistant woke me up and told me about it. I went down and read the article and said, ‘Okay, this is a nuclear bomb.’ I made some calls back, went out running right there in the compound at three in the morning, I thought I was dreaming and that I was going to wake up because this is just not possible.

This was not something I thought I could ever be accused of. Immediately you think, okay, I can connect the dots where this is going to end, not everybody could but I felt that I could then. I started to think about my son in college, my 86-year-old father, my wife and all this stuff takes place on the front page and on TV at every moment. First thing in the morning we’re working and that afternoon I’m told to fly back to the States to see the President.” A few days later, President Obama accepted McChrystal’s resignation.

McChrystal said he then had decided how to command the rest of his life. “I started making decisions sort of on an hourly, daily basis but they start to weave together as sort of a thesis for the rest my life. I think it probably took about a month where I made enough decisions that the direction I was going to take was clear.”

For example, he initially did not want an official Army Retirement Ceremony (commonly called a parade). He thought the pomp and circumstance would make him feel embarrassed by the circumstances of his retirement. But after an assistant suggested the parade was more for those who would be attending, he “started making those decisions and interestingly enough, the more you do that, and the more you take the high road, the more the high road becomes the only option.”

In line with this view, McChrystal has another take on the hero’s journey. In his mind, “there is this narrative construct on the hero’s journey where the hero has a big climax or crisis and then the hero wins in the end. There is always a danger for the kind of work that you’re doing when you end up talking to those kinds of people who have a happy ending. That’s skewed,” McChrystal said. “Not everybody has a happy ending because the crisis can end at different points. You can have the ability to rebound, you can have the time. My story to date, it’s not completely over, has been one that is pretty lucky.”

After retiring from the army, McChrystal founded a consulting firm to help guide companies through the kind of organizational transformation he led in the military. He published his autobiography, My Share of the Task, as well as Team of Teams and his latest book, Risk, A Users Guide. As someone with a Boundary Spanner perspective, McChrystal’s advice based on Risk, and how individuals and organizations fail to mitigate it. They focus more narrowly on the probability of it happenings versus a broader, systemic view of the varied visible and invisble control factors influencing the risk trajectory. He suggests looking at what he describes as a Risk Immune System that involves such control factors as timing, communication, diversity, and structure.

McChrystal’s work also navigates the contours of zealots, like Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, and heroes like Harriet Tubman, the abolitionist who ushered slaves to freedom on the underground railroad. Both leaders, he said, became larger in death than in life. McChrystal said viewing each of these individuals as humans and as leaders, helped his team to “reach a general thesis that leadership has never been what we thought it was. It’s never been the great person theory, list of traits, behaviors. In this complex interaction of factors, the leader is only one part.”

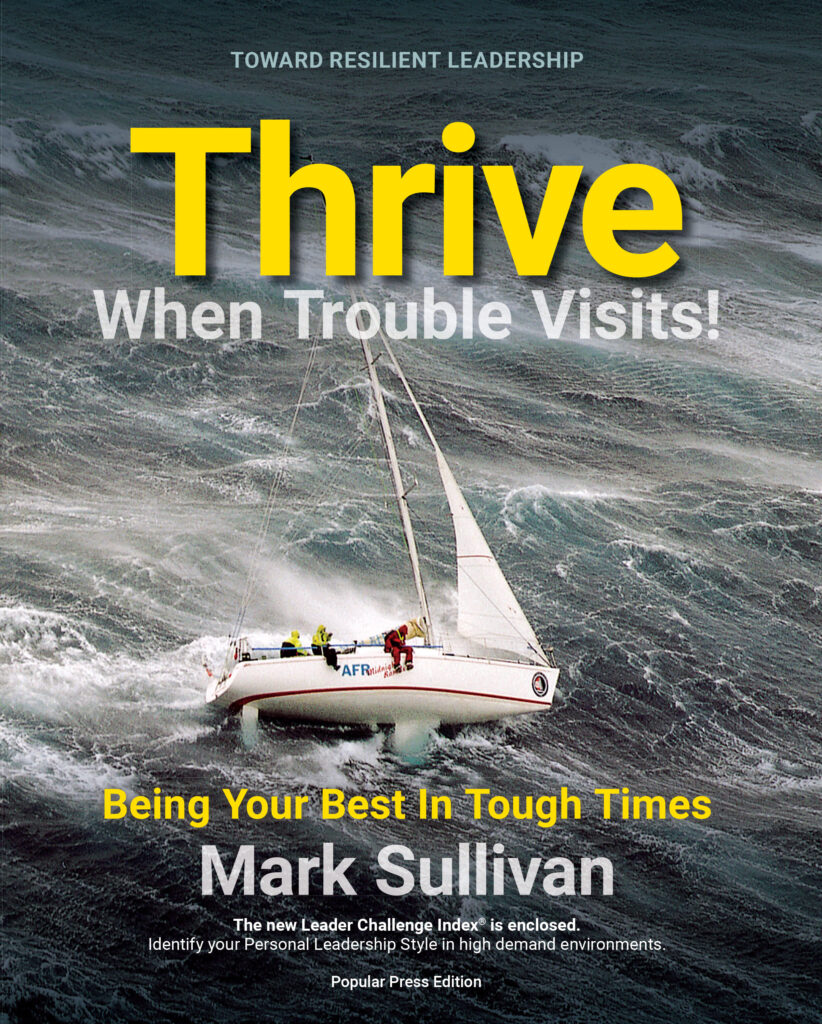

If you enjoyed this story, consider ordering Mark’s new book.

Permission Granted to Distribute by Signature Contributor

Military and Law Enforcement

Adam Carr

Former Special Forces Green Beret; Executive Director of Save A Warrior; MBA, 2019

Adam Carr was a man constantly driven by the need to find some greater purpose. After graduating from The Ohio State University with a bachelor’s degree in 2006, he set out to join the legendary ranks of the United States Army Special Forces, fighting through cracked bones and bloodied boots to endure a test of will that breaks even the most hardened soldiers.

Of the 400 men who joined him in Green Beret training, two years later only 14 endured. Carr was part of an esteemed and rarified club. In the years that followed, the opportunities that lay ahead were endless.

And yet Carr felt only the wave of darkness rolling over him.

Here I was, a 31-year-old man with top-secret clearance, experience leading hundreds of men in combat as a Green Beret, a four-year degree from a great school, a lot of contracting job offers making very good money—well beyond what my friends were making, Carr said. But the purpose just wasn’t there for me. I thought I had peaked at 31. Had my mountaintop moment.

Gaping holes in his personal life were beginning to weigh heavily on him. He’d been deployed for the majority of the past eight years and felt his wife back home in Okinawa growing distant. He barely knew his own children.

I thought, it’s all downhill, and I still have to live this long life without having any purpose, he said. Thoughts spiraled down there for me, and I was in a really dark place.

He knew what that darkness meant. He’d seen too many friends succumb to it. Out of sheer frustration and helplessness, Carr went live on Facebook and, for 24 minutes, shared how he was feeling.

I did it in a way that was very kind of crazy, because I did it online and I did it live for the entire world to see on a public channel, not knowing what would come of it, he said. At this point, what do I have to lose? I’ll fall on this sword if it means I can reach one person. If my story just saves one, it’ll be worth it.

Sharing that part of himself was terrifying and liberating. The video went viral. Thousands of people reached out, including representatives from Save A Warrior, an organization headquartered in Ohio that’s committed to ending the plague of suicide among veterans, active-duty military and first responders. They asked if Carr would meet with them at a café, and he reluctantly agreed.

He arrived to the meeting armed. He’d surveilled the area. He wasn’t about to trust these strangers.

But he found himself moved by their words, and soon he was traveling to California to witness the Save a Warrior experience. A week away brought light to the darkness that haunted him. He learned the essence of what the program called bucket work: It’s like you’re in a boat and you can see land, but there is a little hole in your boat, he said. You have a bucket—and if you don’t start paling that water out of your boat, you’re going to sink and die.

In a way, water had been slowly filling Carr’s boat since childhood.

He’d always been a smaller kid, and bullies seized on that. This was like throwing kindling in the fire. It made him want to work harder than ever to prove himself. A dean at his high school took a look at the Stanford ball cap Carr wore and said people from their school don’t get into universities like that. Even in the Army, Carr was constantly hearing he wasn’t good enough: You’re probably not going to make Special Forces, a major once told him. Barely anybody gets through. You have to be the best of the best. But you’ll be a good infantryman.

He found himself fueled by those who underestimated him. As a kid, he dreamed of being a superhero who stood up to the bullies. As a Green Beret, he hoped to be a model for others who might feel overlooked or helpless.

I may not be the biggest, but I’ll never give up, Carr said. Because somebody else out there might be watching, and I want to inspire the little guy or somebody out there who doesn’t believe in themselves.

But while he paddled furiously toward his goals, Carr failed to see the water rising in his boat. Despite his impressive accomplishments, he was sinking. Joining Save A Warrior—he would ultimately become executive director of the organization—helped him see that, and his raw confessional videos helped him share it. For the first time, on a public forum no less, he let others see the parts of him he’d always tried to hide. He found that his vulnerability was the path to connection.

He became a different kind of superhero.

Being vulnerable and sharing how I felt—instead of trying to be He-Man or John Rambo, like everybody thought that I was—really allowed me to connect with people in a way I’ve never been able to in my life, he said. I’ve always been the one that I need to bear the burden. I don’t want to bother anybody else. I need to portray myself as strong. What I’ve really learned is that a real man can be vulnerable with boundaries. That’s true courage and true strength—being able to connect with somebody else and put down your walls.

Carr’s story is full of valuable life lessons, and maybe the biggest is this: You don’t have to be the box you were born into. You are in fact the director, producer and starring actor of your very own movie called life. Out of possibility and declaration, one can create a powerful, joyful, self-fulfilled life.

Also, you don’t have to be a Green Beret to find that kind of strength. Look around. Support might actually be reaching out to you and inviting you to a café. If it’s not, ask for it. Admit you don’t have the answers. You’ll probably be surprised to find out how many people are just like you—and how many have been waiting for someone else to say it out loud.

When Carr shared his first video, one of the thousands of people who reached out was a woman he never met. She said she, like Carr, was lost in the darkness. She was planning to end her life that day until she saw Carr’s video and made the decision to push forward.

In that moment, Carr realized he’d finally found his purpose—his true purpose.

If you enjoyed this story, consider

nec gravida tempor dolor convallis. facilisis in nec gravida tempor dolor convallis.

facilisis in facilisis tempor libero, orci cursus nec orcial nec gravida tempor dolor convallis

2-way access:

- To purchase the THRIVE book separately, click “Buy Now”

- Want to purchase only the Toolkit? Click on the ‘Get Toolkit’ button to access it instantly