Dr. Ehud Mendel

Israeli Air Force veteran, American Neurosurgeon, Family Man, Professor, Clinical Director

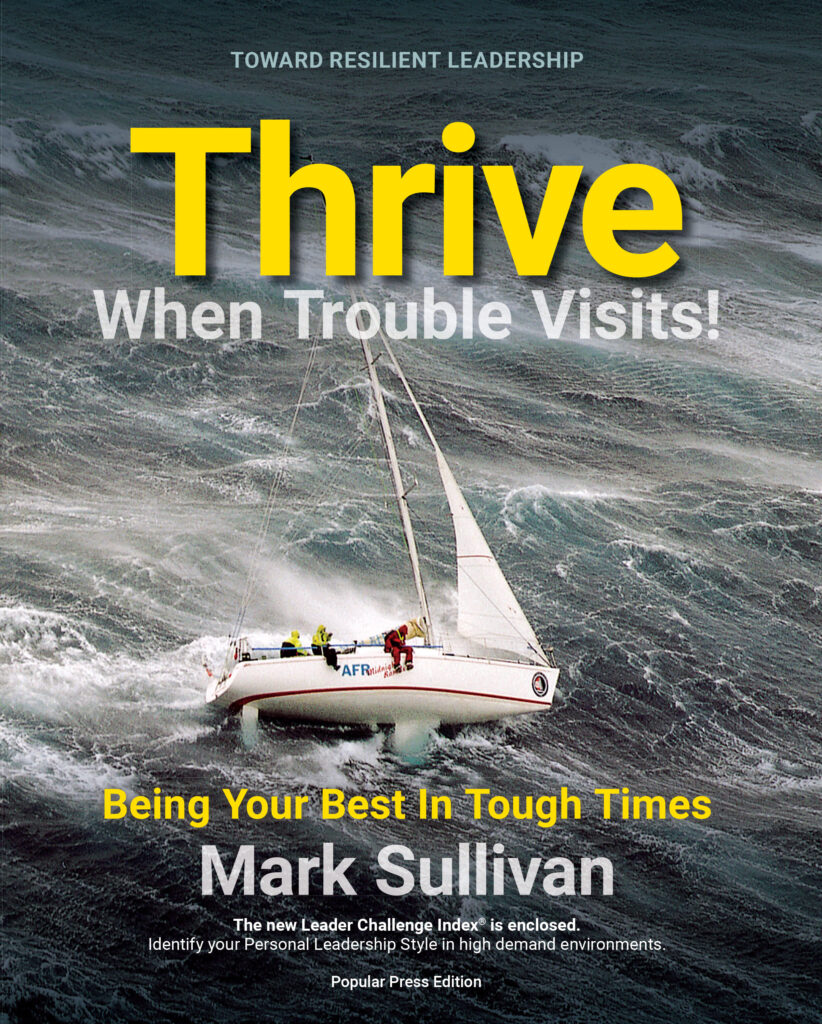

If you enjoyed this story, consider ordering Mark’s new book.

Permission Granted to Distribute by Signature Contributor

Business, Science, and Health Care

Ehud Mendel

Israeli Air Force veteran, American Neurosurgeon, Family Man, Professor, Clinical Director

The first time I met Ehud Mendel, he walked out of my class within the first 20 minutes.

I wasn’t alarmed, at least not at first. Students often step out to use the bathroom or grab a drink, and Mendel had left behind his things. But as the minutes slipped by, I began to wonder.

When he returned a half hour later, I wasn’t sure what to think.

During a break, he came up to introduce himself. In a distinct Israeli accent, he told me he was a doctor at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, a neurosurgeon, in fact, and that he was pursing his MBA at Ohio State so he could spend time with his son in the same program.

He said he could never be too distant from his job, and that occasionally he’d need to leave class to take phone calls from his team in the emergency department.

During this particular call, he’d spoken at length with a mother reeling from the shock of learning that her son had been shot in the head and was now clinging to life in the emergency department.

“I hope you don’t mind if I take those calls from time to time,” he told me.

I was speechless. Of course I didn’t mind. But I did want to know more—not just about that call, but about the man who stood before me.

Mendel turned out to have quite the life story. It began decades ago in Israel.

“We’re moving to America.”

Mendel’s ears perked up, unsure if he had heard his father correctly. “Did you just say you’re moving to America?”

His father had been working in the desert oil drilling business all his life and had just lost his job. His options were to re-invent himself or move halfway across the world, to Louisiana, for work. He’d chosen the latter.

Mendel’s heart sank. At 18, he knew he couldn’t join his family—he needed to finish out his required service in the Israeli Air Force—and he wasn’t sure how long it would be until he would see his father, mother and youngest brother again. But he also respected his father’s decision. He knew his dad didn’t feel he had a choice. The family headed to the United States, and Mendel and his middle brother, who was still in high school, stayed behind.

Five years passed, and Mendel faced a difficult decision of his own. His family wanted him to move to the United States. His mom, feeling like one of the only Jews in Cajun country, was desperately lonely. But in Israel, there’s a significant stigma attached to leaving the country. Many Israelis look down on those who make their lives abroad, branding them yordim—“those who descend.”

Plus, there was a girl.

“I was in love with a woman and my plan was to go to university in Israel, but I said I was going to give the U.S. a trial of six months,” he said. “She was not willing to leave Israel. She told me, she would meet me in six months. I’ll never forget: Her mom called me and was very upset about my choice. I knew the relationship was over.”

He headed to Louisiana and reunited with his family, finally seeing them again for the first time in five years. He enrolled at Nicholls State University, a small public university in Louisiana close to his parents, intent on earning stellar grades and graduating a year early. But first, he had to adjust to his completely unfamiliar new life.

“It was shocking,” he said. “I had just finished the military, I was 23, and I found myself in college taking English 101 and Chemistry 101. A few weeks ago I was in the military and now I’m in Louisiana taking classes with 18-year-olds thinking about what bar they’re going to go to. I was the only Jewish person I knew at Nicholls State and it was a significant culture shock. English language wasn’t my first language. I lived with a dictionary in one hand and a tape recorder in the other. It was tough.”

But his uncomfortable surroundings had provided him an extraordinary opportunity. In Israel, Mendel’s future would have been assigned to him—he would he been told which career he would pursue. In America, he could be anything he wanted. He’d never even considered becoming a doctor, but as he reflected on his options, he found himself drawn to medical school. He finished his undergraduate work at Nicholls in three years with a degree in Chemistry and applied to schools across Louisiana.

“I knew I wanted to become a surgeon,” he said. “My dad always thought that to be successful you had to do something with your hands. You need a table, you build a table. Your car breaks down, you fix it. So I became very comfortable using my hands. I became ambidextrous. When I went to medical school, it was natural for me to know I needed to do something with my hands. Becoming a surgeon seemed like the right career choice for me.”

Mendel got accepted to Tulane University, but his parents didn’t have the money for private-school tuition. His father again offered a sacrifice: he’d sell their house, and the family would move into a rental to make sure the eldest son received the education he needed to pursue his dream job. Mendel was relieved when his acceptance letter from Louisiana State University, a much more affordable option, finally arrived in the mail.

He graduated from LSU in 1991 and a week after graduation married the woman he had met at Nicholls and dated for seven years long distance while she pursued her education in law. The two of them then moved to California so he could start his seven years of neurosurgery training at the Los Angeles County+USC Medical Center, which included a year of fellowship training in complex spine surgery in University of Florida in Gainesville. During the seven years of training, they started a family, welcoming a son while in California and a daughter in Florida.

More moves followed: Iowa, then South Carolina, then Houston, and finally Ohio in 2006, where he became the Director of the Spine Oncology Program at the Ohio State Comprehensive Cancer Center – James Cancer Hospital and Neurosurgery Clinical Director of The Ohio State University Spine Research Institute.

While the move to Columbus brought some stability, Mendel’s work is anything but predictable. It’s a high-demand, high-stress existence that can leave him shaking off the massive adrenaline spike of a 12-hour surgery. He looks forward to hitting the Crossfit gym, hopping on his bike for a long ride or just talking to his kids at the end of the day —anything to peel his mind from what just happened in the operating room.

“This job is not for most people,” he said. “You can make huge differences in people’s lives, but you can also hurt them if things don’t go well. The distance between success and failure is very small, and the window of opportunity is critical. This is the life of a neurosurgeon.”

But this is the job for Mendel. His fellowship director said he’d be done after 10 years, but he’s been at it more than twenty-two. He’s taken on the heartache of patients who can’t be saved and the overwhelming joy of those who experience astonishing recoveries. He uses his hands to do the extraordinary.

When I think about what makes Mendel so good at what he does—adept not just at the delicate intricacies of brain and spinal surgery, but also able to bear the physical and mental toll of his life-altering work—I think about the path that led him to Ohio State. The way he left his comfort zone again and again, picking up and dropping into a new country, a new state, a new culture. Each time, he not only adapted—he thrived. Through his resiliency, he molded his life into the most rewarding existence he could envision, and in doing so, he’s touched innumerable lives.

In life, you too will find yourself facing difficult decisions. You’ll occasionally be immersed in the unfamiliar. It won’t always feel good. You’ll be tempted to shy away from those situations, to instead seek the things and the people you know.

But think about what might happen if you, like Mendel, search for the opportunity in your uncomfortable circumstances.

How many lives might you touch?

If you enjoyed this story, consider

nec gravida tempor dolor convallis. facilisis in nec gravida tempor dolor convallis.

facilisis in facilisis tempor libero, orci cursus nec orcial nec gravida tempor dolor convallis

2-way access:

- To purchase the THRIVE book separately, click “Buy Now”

- Want to purchase only the Toolkit? Click on the ‘Get Toolkit’ button to access it instantly